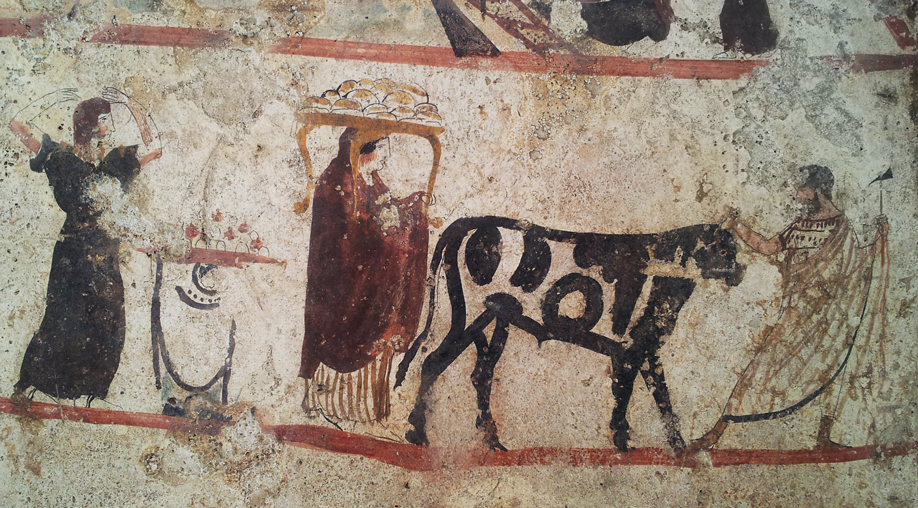

Although preparing food was an important daily activity, information about the Etruscan cuisine is very rare. There is no Etruscan literature about food or dining. We only have some shreds of literature from ancient Greeks and Romans who wrote about the Etruscans. And they were not very positive: Etruscans were spineless and spend whole days at the table drinking, eating and feasting. Archaeological finds in Etruscan villages and frescoes in Etruscan tombs give us a more modest image of daily life and the role of food in it.

Etruscan cooking

Archaeological finds do not show us sophisticated Etruscan kitchens, like the ones from the Roman era. But they do give us pots, pans and cooking utensils. The Etruscans used grills, spits, stoves and ovens to cook their food. Ovens looked a lot like the pizza ovens that are still used today, but there were also small portable ones. Stoves came in different shapes and sizes with possibilities for slow cooking or more intense heat. What I find very interesting is that they also cooked ‘sub testu’, under an earthenware pot. They placed bread or vegetables on a plate and covered it with a bell-shaped pot with a handle at the top like I am going to do in the recipe below.

Cooking utensils were divers. For example mortars, mills, grinders, colanders, graters, knives, cleavers, hooks, trays, ladles and containers.

Etruscan ingrediënts and dishes

Etruscan staple foods consisted of cereals, legumes and vegetables. They produced and exported it in large quantities. Most eaten cereals were barley, emmer and oats and in the legume section peas, broad beans and vetch. Cultivated as well as wild fruits like grapes, figs, plums, pomegranates, pears, olives and nuts were on the menu.

The use of animal products was limited and often related to rituals, especially for the poorer classes. Fish was eaten most in coastal areas, although freshwater fish was also appreciated. Milk from sheep, goats and cattle was drunk and made into cheese. Their meat was eaten, as was pork. Eggs and meat from chickens, ducks and doves were cooked. The Etruscan diet was extended by eating game, of which there was a lot in their region. They hunted boars, hares, ducks, deers and foxes of which bones are found in excavations.

Meat and fish were cooked, roasted or stewed as were vegetables. Cereals and legumes ended up in stews and soups and were made into flour for baking bread, flatbread and pancakes for example.

Etruscan wine

Etruscans were skilled winemakers and their wine was appreciated in many regions around the Mediterranean. Production started in Etruria in the third quarter of the seventh century BC and soon the wine was exported throughout the region. The beverage was especially for the upper classes. They drank it at the banquet as is seen on frescoes in Etruscan tombs. Drinking utensils show that wine was mixed with water and even that wine games were played, like the ones in Ancient Greece. This most appreciated drink calls for some food to pair it with.

Cheese bread with olive puree

Not a single Etruscan recipe is hand down to us. But we know what they ate and with a bit of inspiration from early Roman cuisine (De agricultura of Marcus Porcius Cato from the second century BC), we can make a nice dish with appetizers that pairs perfectly with their beloved wine: a firm cheese bread baked under a clay pot with a puree of olives and fresh herbs that Cato named epityrum.

Like the Etruscans, we are going to use a ‘testa’ for baking our bread: an earthenware pot which you put over your loaf of bread. You can use a simple (non-glazed) flowerpot as I did. Soak it in cold water for 30 minutes before you use it.

Vary with the seasoning of the bread and olive puree to your taste, as the Romans did, and I assume Etruscans did too. For example caraway or cumin seeds in the bread and your favourite green herbs in the puree.

Bread

1 cup / 250 grams ricotta

1 egg

1 tbsp honey

1 cup / 150 grams spelt flour

1 tbsp fennel seeds

bay leaves

Preheat your oven to 400F/200°C. Stir the ricotta until almost liquid. Beat the egg. Pour the egg and honey into the ricotta and stir until all is combined. Add the spelt flour and fennel seeds and knead everything together until you have a dough. Form the dough quickly into a ball or 8 little balls and flatten them out a bit. Put the bread on the bay leaves on a baking tray. Put your testa over it and bake in the preheated oven. The big loaf for 45 minutes and small ones for 25 minutes.

Olive puree

1 handful of green olives (pitted)

1 handful of black olives (pitted)

4 springs of fennel leaf or 1 tbsp fennel seeds

10 springs of fresh coriander

1 spring of rue

2 springs of fresh mint

1 tbsp white wine vinegar

3 tbsp olive oil

1 tsp ground cumin

Ground the olives in a big mortar or chop them very finely. Chop the fennel, coriander, rue and mint and add to the olives. Add vinegar, oil and cumin and mix everything together. Add more oil or vinegar to your taste.

Cool the bread. Put the olive puree in a bowl. Serve together. Optionally add slices of pecorino cheese to your plate for a complete dish to pair with a good glass of fine Etruscan wine.

This article was published in Ancient History Magazine.

Photography: Jeroen Savelkouls fotografie