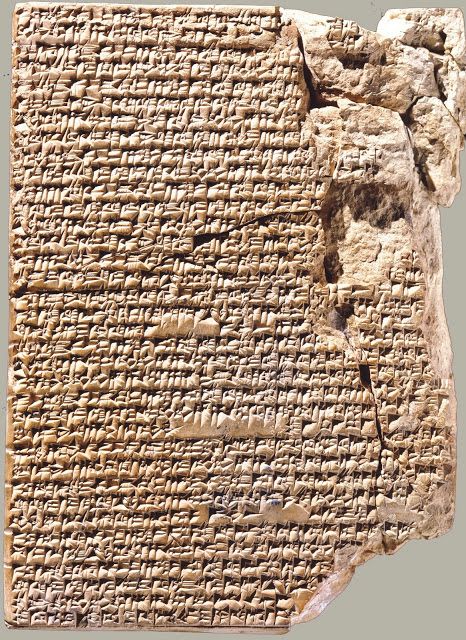

There is not much written information about ancient cuisine from Near Eastern civilizations. Art and archeological remains reveal extended cuisines in, for example, Ancient Egypt, but not a single recipe is handed down to us. There is one exception: Mesopotamia cuisine. Three clay tablets with recipes from Mesopotamia are preserved. Along with other clay tablets they give us a good impression of what was eaten 4000 years ago.

Mesopotamian recipes

There are only three remaining ancient Babylonian culinary tablets, dated ca. 1750 BC and written in Akkadian. They reveal the world’s oldest known recipes. They are preserved in the Yale Babylonian Collection. One of the tablets, badly damaged, reveals three recipes with meat dishes (YBC 4648). They all look like stews. A second (YBC 8958) provides us with seven bird recipes, with even clues for preparation. A third tablet (YBC 4644) has 25 short recipes for stews or soups written on it. The recipes looks like little shopping lists. We are going to cook one of them. The variety of ingredients and sometimes complex preparation suggest that they were intended for the royal palace or temple.

The Mesopotamian diet

The diet of the ancient Mesopotamians was very extensive. A huge vocabulary (written on 24 clay tablets) lists 800 entries of food and drink. There are more than hundred soups and stews, 18 kinds of cheese and 300 kinds of bread.

They eat a lot of grains, fruits and vegetables. Bulbs, roots and onion related varieties (leek, garlic and a kind of spring onion for example) were eaten a lot. Local fruits included grapes, figs, dates, pomegranates and even apples and pears. Olives, sesame seed and linseed were eaten and pressed for oil.

Meats were also on the menu. Lamb, beef, pork, deer and fowl are listed on the tablets, as are their by-products eggs, butter, lard and milk. Sea fish, freshwater fish and shellfish are mentioned, along with turtles and grasshoppers. Grasshoppers were pickled, it seems. A lot of different birds were eaten. On the clay tablet with seven bird dishes, there is a recipe for a pie with little (singing?)birds in it. The recipe even mentions how to prepare the dough, with samidu. Which is probably fish sauce, similar to the one we know so well from Roman cuisine. I made this recipe once with pigeons, using fish sauce in the dough. It was very tasty!

To flavour their dishes, the ancient Mesopotamians used quite a lot of seasonings. Spices are not mentioned, but salt, herbs, honey, vinegar, resin (from tree sap) and liquorice are.

Cooking from clay tablets

Well then, let’s cook, you are probably saying by now. There are some obstacles that we have to overcome first. The clay tablets are not complete; there are holes and cracks in them. Another issue is that not all the ingredients are available to us today. There is a lot of discussion about the meaning of some (quite essential) words. Also, the writers of the clay tablets didn’t provide measurements and cooking methods.

Finally, there is no conformity about some words in the available translations of this recipe. I cannot clarify this, because I can’t read cuneiform script. For example, the word ‘salt’ is sometimes translated as ‘vinegar’. I use both ingredients in the recipe. Dodder is also unclear, but some think liquorice is what is meant. It gives a beautiful taste to this recipe, so please use it. Samidu is translated by some as a kind of onion, by others as semolina and by some as fish sauce. I choose fish sauce in this recipe. And what about kisimmu? Maybe it is kišhik. A mixture of dried yoghurt and grain (today, wheat is used) that is formed into little balls. Maybe it compares with the kishk that is still produced in Lebanon and also used in Syria, Jordan, Iran and Turkey. It gives stews a deep, complex flavour, and it also binds the liquid a bit. I found it in a Persian shop and fell in love with it.

But I love a challenge. Don’t you? A few years ago, with students from my historical cooking course, I plunged into a garlic soup, a turnip stew, a bird pie, sebetu bread (filled with onion, leek, garlic and – yes! –fish sauce), mersu (a kind of date-nut balls) and my favorite: a mutton or lamb stew. I still make this stew at home! So let’s cook this stew from the clay tablet with 25 stew recipes (YBC 4644). Translation by Jean Bottéro:

Lamb stew. No other meat is used. Take water, add fat, dodder as desired, salt to taste, onion, samidu, coriander, leek and garlic, on the fire. From the fire add pressed kisimmu. Cut the meat and serve.

Babylonian lamb stew

Ingredients

100 g belly fat

600 g lamb (for stew)

2 tbsp olive oil

700 ml water

1 piece of liquorice, bruised

2 tbsp wine vinegar

1 tsp salt

1 tbsp fish sauce

1 onion, finely chopped

1 spring onion, in little rings

½ bunch coriander, finely chopped

1 leek, in thin rings

4 cloves of garlic, finely chopped

circa 1 tbsp or 2 balls of kišhik

Preparation

Cut the belly fat in little pieces, and dice the lamb. Heat the olive oil in a casserole dish over a medium-high heat. Add the belly fat. Let it brown on all sides. Take the belly fat out of the casserole dish, pour in a little extra olive oil, and add the lamb. Let this also brown.

Add the belly fat to the casserole dish, with water, liquorice, wine vinegar, salt, fish sauce, onion, spring onion, coriander, leek, and garlic. Bring to a boil. Lower the heat and let it stew for at least two hours. The meat must be tender.

Crumble the balls of kišhik into a fine powder. Use a mortar for his. Add the kišhik powder to the stew and let it simmer for fifteen more minutes.

Chop a bit of fresh coriander to top of the stew. Eat the stew with rice, couscous, or bulgur. It is even better the next day, as all stews are!