The focus of the 18th-century nobility was aimed at France. Whatever the French wore, ate and did was copied at the Dutch courts. These French influences are also visible in the cuisine bourgeoise, or the kitchen of the middle class, that evolved in the 18th century. The middle classes, especially the upper-middle class, looked up to the nobility and copied everything they did.

Kitchen Maids

Approximately mid-18th century, a series of cooking books appeared in the Netherlands that were written by kitchen maids. Remarkable, because the cookbooks that had been published before were usually written by real cooks or doctors.

Many nobility households had dozens of employees, while the households of the middle classes only had one maid perhaps. Apart from the regular household chores, this maid also ran the kitchen. Her ‘madam’ usually carried a handwritten cookbook with recipes she picked up at family gatherings or when she visited friends. Popular recipes that many well-off middle-class people liked were written down by the kitchen maid so she could prepare it for her employers or whenever there were visitors. Many recipes have been preserved in family archives.

The cookbooks written by kitchen maids are not written by the actual kitchen maids themselves. The recipes in these books are often gatherings of recipes collected by the kitchen maid’s madam. These madams wrote the recipes down for the kitchen maid, or as an inheritance for her offspring.

Cookbooks

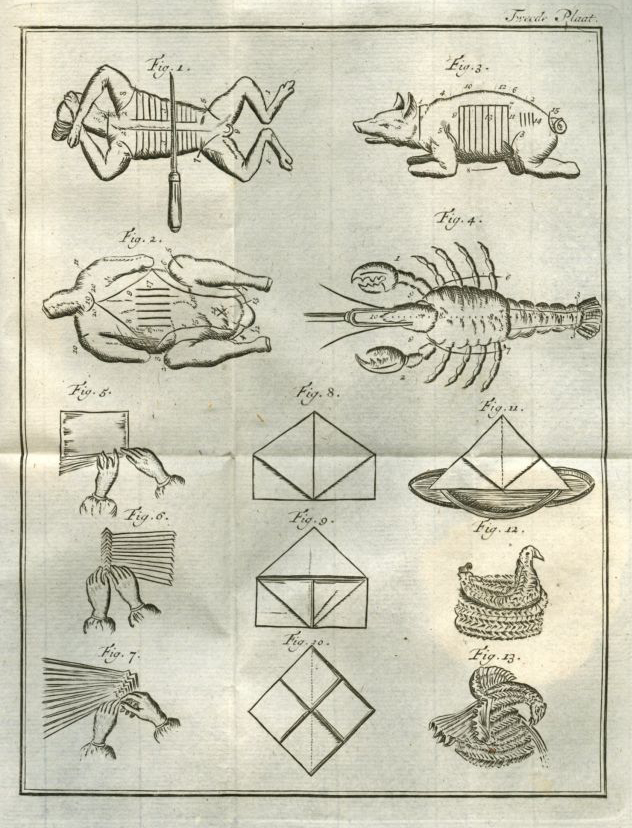

The first kitchen maid’s cookbook appeared in 1746 in Amsterdam: De volmaakte Hollandsche keuken-meid (the complete Dutch kitchen maid). Apart from the 300 recipes, there is also information about how to cook and present these meals. This means that dinner was supposed to happen according to the service à la française. Dishes needed to be served in a sequence of courses, simultaneously and according to a symmetrical system. Also, the cutting of the meat, folding the napkins and how to bring a toast was shared with the kitchen maid and her readers.

In 1754 De schrandere Stichtsche keukenmeid (The smart Stichtsche kitchen maid) was published in Utrecht, followed by De nieuwe welervarene Utrechtsche keuken-meid, confituurmaakster en huis-doctores (The new well-to-do Utrechtsche kitchen maid, jam maker and house doctor) in 1769. This book had over 500 recipes and got reprinted in 1771, 1772 and 1774. In 1744 there was even a sequel called Vervolg op De nieuwe welervarene Utrechtse keukenmeid (The new well-experienced Utrecht kitchen maid) which had even more recipes for kitchen purposes and a very elaborate medicine cabinet.

Perhaps the most popular kitchen maid’s cookbook was printed in 1756 in Nijmegen: De volmaakte Geldersche keuken-meyd (The complere geldersche kitchen maid). It got reprinted eleven times between 1756 and 1865 that got distributed to a lot of different cities. De Geldersche Keukenmeid had more recipes in every new version, eventually the book had over 700 recipes. They did get many recipes from their predecessors.

In Leeuwarden in 1772 a kitchen maid’s cookbook appeared that was a little different than all the others. It was called: Het Volkoomen Neerlandsch kookkundig woordenboek voorgesteld in Friesche keukenmeid en verstandig huishoudster door mejuffrouw Catharina Zierikhoven. Could this be an actual kitchen maid that wrote a cookbook? The book is even alphabetically ordered, including faulty French titles. Or did another anonymous author write a cookbook with ‘kitchen maid’ in the title to appeal to the public?

French influences

Several culinary manuscripts got published in the 17th and 18th century in the Netherlands. They were published in French and Dutch. The famous Le Cuisinier François by François de la Varenne, which was the predecessor of the French cuisine, was published in the Netherlands in 1701 with the title De geoefende en ervaren keukenmeester of de verstandige kok (the trained and experienced kitchen master or the sensible cook). Work from the famous François Massialot (Le cuisinier royal et bourgois) and Vincent La Chapelle (Le cuisinier moderne) were very popular in the Netherlands.

The kitchen maids copied a lot from the French books. The most popular recipes came from La Varenne. A remarkable fun-fact is that many titles from the French recipes were misspelt when they were copied. These are often more phonetically spelt version of the original French titles. This makes it even more surprising that the supposedly only real kitchen maid’s cookbook, by Catherina van Zierikhoven, is written in perfect French.

Even though people copied recipes from French cookbooks, the message to the audience was still that Dutch recipes were much healthier, tastier and more economical than foreign recipes. Well…economical? The recipes are filled with recipes that were quite expensive at that time.

Traditional cookbooks with new twists

What is surprising about the kitchen maid’s cookbooks is that they are like transitional cookbooks between the old kitchen traditions and the nouvelle cuisine from the late 17th and 18th century. There are a lot of medieval influences like pies, sugar in savoury dishes and dishes that looked like they were made from something different (minced fish in the shape of ham or calf meat in the shape of an eel). Recipes from the 17th-century cookbooks like De verstandige kock (1667) (the sensible cook) and het Koock-boeck oft familieren Keuken-boeck (1612) (the cookbook or the family kitchen-book) by Antonius Magirus are everywhere: simple recipes that did not have a lot of spices and did not have to be fancy looking.

The cookbooks had new recipes, new ingredients and new cooking techniques as well. Personally, I find kitchen maid cookbooks interesting because of the number of sweet recipes. Deserts, pastries, confectionary and cookies. But they also show new innovations like broth cubes and cubes made from orange juice. Much like the increased number of soups, stews and vegetable dishes. We find recipes with salsify, pumpkin, celeriac and truffle in the Utrecht’s kitchen maid. The Holland’s kitchen maid serves Brussels sprouts, peas and the Frisian kitchen maid has the first potato recipe.

Despite coffee, tea and coffee making their way into the 17th-century kitchens in the Netherlands, we only find the first recipes with these new ingredients in the 18th-century cookbooks. Recipes like coffee pie, cookies for tea time, and chocolate crèmes (chocokaad-craim). Another thing about these cookbooks that I thoroughly enjoy is the names of the dishes. That is why I give you a recipe for cookies with the delicious name ‘wespennesten’ (wasp’s nests).

Ingredients

250 grams of

flour

200 grams of sugar

250 grams of cold butter

1 lemon

½ egg, beaten

200 grams of raisins

1 tsp cinnamon

2 tsp granulated sugar

Preparation

Put the flour and sugar in a big bowl. Grate the lemon peel and add it to the bowl. Chop the butter into small cubes and add these as well. Make a crumbly dough by mixing it with your hands. Add the egg and knead it until it is a cohesive dough. Make a flat circle of the dough and let it stiffen up in the fridge.

Spread the dough into a big square that is approximately 1 cm thick. Spread the cinnamon and sugar on top and add the raisins next. Roll up the dough and cut it up into slices. Put them onto a baking sheet on their sides. Bake them at 180 °C for 15 – 20 minutes. Well, what do they resemble? Right!